One

Thank God for language arts teachers who give students the opportunity to discover that fiction provides insights into human nature. Without that knowledge, I probably would never have read the passages below. Consequently, I don’t know how I would have approached, much less resolved and found a way out of, a deep-rooted professional crisis.

Two

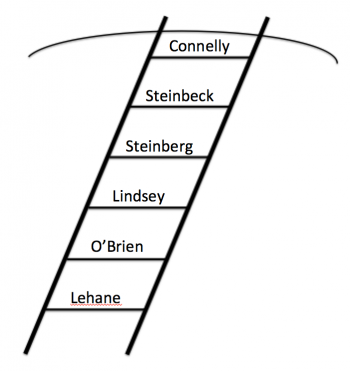

Lost. Forgotten. Neglected. None precisely describes the fading connection between my hand at work and my heart at work. I don’t think anyone’s noticed. This “actress” has learned the lines you’d like to hear and delivers them on cue. Yet, I can’t sustain the mask. To get out of this hole I need to build a ladder. Every sentence in this passage from the Dennis Lehane short story, Gone Down to Corpus, from Coronado Stories (P.S), provides a rung:

About five years back, we break down on Route 39, just me and my mother, and we’re standing there in the white heat with the dirt, dying of thirst for a hundred flat miles in every direction and Daddy’s piece-of-shit truck gone gasping into a coma beside us, and my mother puts a hand over her eyebrows to scan the emptiness and she looks like any fight left in her just up and died with the truck. She looks like she can remember a time before she got where she is now, and all those different who-she-could-have-beens fork out like trails before us, branching off and branching off into all that Texas dust until there’s so many of them they just have to fade away to nothing or else she’ll go blind trying to keep count.

Her voice is dry and torn when she speaks, and it takes a couple breaths to get the words out: “Remember, Sonny, times like these— remember that somewhere there’s someone worse off than you. You’re always richer than someone.” She tries for a smile as she looks over at me. “Right?

The next rungs come from a paragraph in Going After Cacciato, by Tim O’Brien, that show the vital link between integrity and inner longing that I’m trying to reconnect:

He was a professional soldier, but unlike other professionals he believed that the overriding mission was the inner mission, the mission of every man to learn the important things about himself. He did not say these things to other officers. He did not say them to anyone. But he believed them. He believed that the mission to the mountains, important in itself, was even more important as a reflection of a man’s personal duty to exercise his full capacities of courage and endurance and willpower.

Sadly, though, as experience accumulates over three decades, every next “new” thing and person seems familiar, worn, and too, too predictable. My thinking diminishes to unadventurous predictions that become self-fulling prophecies. There is little at risk because there is little of me in the game, so who needs courage and willpower? I feel cynical and superior. I go to my son’s bookshelf and find my old copy of In the Lake of the Moon, by David L. Lindsey. I open to the page containing a father’s counsel to his son, Stuart, a homicide detective on one of his first cases:

You’ve chosen a hard profession, Stuart,” his father said. “You’re going to see a lot of peculiar behavior that you won’t understand, and you’ll see it so often you’ll get to the point you can predict it. And then you’re going to believe you do understand, and you’ll want to pass harsh judgments. But the reality is that we can never really penetrate the truth of why some men do the strange things that they do. We can only view such men with pity and compassion, and remind ourselves that none of us are exempt from error, sometimes serious error, from playing the fool. When you look at these men try to temper your judgment with humility, with a modest nod to your own ignorance of the uncertain ways of the heart.

Humbled at being called out for my ignorance (and self-indulgence), I shove cynicism and superiority aside. My ladder passes the halfway point.

Three – an aside

In Travels with Charley, John Steinbeck wrote of the “endless possibility of words.” He referred, specifically, to the “idioms, the figures of speech that make language rich and full of poetry of time and place.” But can’t the endless possibility of words also include, particularly in fiction, the power that comes from walking in another’s shoes?

I don’t know if I could voice that claim if it hadn’t been for a few minutes in 1969 that changed my life forever. In Mrs. Reams’ seventh grade language arts class we read Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men. Reading silently one day, I became Lenny as he kills the rabbit. As if my own hands squeezed the life out of the creature, I discovered the helplessness of passing one-way thresholds, of ringing bells that can’t be unrung, as Michael Connelly writes in The Fifth Witness. (Or was it The Brass Verdict?) I also discovered that it’s worth paying attention to books.

In later years I also found that fiction brings clarity to our lives by helping us explore the deeper meaning of our days. So illustrates Milton Steinberg in As a Driven Leaf (one of the best novels ever). The main character, first century Rabbi Elisha ben Abuyah, rejects his faith in favor of Hellenistic rationalism, only to realize the bitter futility of empirical reasoning as he tries to comfort his beloved at the moment of her death. Early on his path, he explains to a confidant that he knows he is on the road to self-destruction:

[T]he stuff of spiritual peace is of a much less heroic character. A man has happiness if he possesses three things – those whom he loves and who love him in turn, confidence in the worth and continued existence of the group of which he is a part, and last of all, a truth by which he may order his being. … These are the qualities that are passing from my life.”

Four

The works of Lehane, O’brien, and Lindsey, illuminate my crisis, and those of Steinberg suggest that a resolution lies not within myself, but through my attachment (sorry, Buddha) to people, the future, and faith.

But it’s up to Lincoln lawyer, Mickey “the Mouth” Haller, in Michael Connelly’s The Gods of Guilt, to model concrete steps I can take to strengthen those attachments, finish the ladder, and finally climb out of this hole:

Everyone has a jury, the voices they carry inside…Those I have loved and those I have hurt. Those who bless me and those who haunt me. My gods of guilt. Every day I carry on and I carry them close. Every day I step into the well before them and I argue my case.

So a few days ago, I resolved to ignore my self-obsessing. Instead, I titled a page in a journal with my with my son’s cherished description that, “You are the one who pushes back.” Underneath that, I wrote: Integrity.

Then I listed my professional and personal commitments and to each made a promise. I sat my jury that includes family members, dear colleagues, students, Jesus, and The Profession. I now argue my case daily and listen to their counsel. Their verdict doesn’t always go my way.

But I’ve stepped onto solid ground from the top rung of the ladder.

Five

Thank God for language arts teachers. May they know the difference they make.

Comments 1

Wow. I am almost in tears, Sandy. The fact that you are able to tie this intensely personal reflection and literary synthesis back into a manifesto for the teaching of fiction is simply the icing on the cake. That is a terrible cliche to bring into such a well-read meditation. This not only rang true, it resounded for me. It also made me miss teaching the more literary aspects of fiction, but as you point out, sometimes simply giving students the opportunity to step into another’s position for a few moments can create worlds of new experiences for them. In the new world I have entered of basic vocabulary acquisition and grammar structures, your piece also inspires me not to neglect opportunities to discuss or at least bring to students’ attention the themes and ideas in what we are reading.

Amazing!