The red dot measured eight inches in diameter. Pretty small considering it was shot from a light 3 miles away.

Small town fun on a summer’s eve and the seeds of a future.

Call it 1974, place it in Silver City, NM. We had neither video games nor smart phones. Our social network was face to face and included Bob, a teacher at the rival high school one town over. And Bob had stuff, and time. This time it was a laser – the real thing – and probably the last one I saw for 20 years.

On the night in question we formed two teams. One aimed the laser out of Bob’s van, parked up on 180 near the A & W. The other set up at the water tank, above the local college’s dormitories. With citizen band radios and binoculars we coordinated the shot. There was a lot of, “Left, left, NO! YOU MORON! TOO FAR, TOO FAR!” It finally landed and blew our minds away.

Later, Bob didn’t lecture us on optics or coherent light. But we had questions and he had answers.

Bob had more stuff in his lab, and sometimes he’d take us there. Most was army surplus like the EKG that would print out a tape of our pulse. Bob would put us through jumping jacks, pushups, and resting periods, and we’d see how our pulse responded. He had the first calculator I ever saw. It cost $100, was the size of an IPad, and could only do 4 functions. We played with it for hours.

He had stuff at his house, too, like the disassembled motorcycle that never left his kitchen. Once he had an early sound effects machine. You’d put on headphones and try to carry on a conversation as Bob turned dials that distorted or delayed your voice. Since what we heard was so different than what we said, our circuits got fried, and in no time we couldn’t speak coherently. The effect was hysterical and lasted a good while after we took off the headphones. (We were all afraid to go home because we sounded drunk.)

Bob had time to listen and ask the questions through which we turned our childish conceits into adult aspirations. But he could lay things on the line. “College isn’t high school. You can’t blow off a class, cram the night before the final, and walk off with an A. You go over your notes every day and start reviewing intensely a week before your tests, or you won’t make it.” Going into my first ever college exam, I followed his advice and got the highest grade in the class.

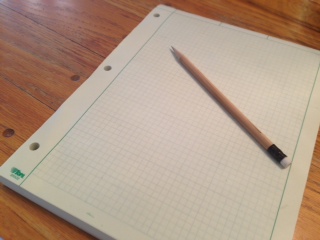

He set us straight on research. “You think research is going to the library and rehashing what someone else already did. Real research starts with a ream of paper, a sharp pencil, and a question you can’t look up because no one’s ever asked it.” Norman Packard spent time with Bob before I knew him. He started asking questions that no one had ever asked and became a founder of Chaos Science and a leading investigator of Cellular Automata.

Bob cast a wide net. Once while visiting Silver City, the clutch in my Honda went out. The very young mechanic who fixed it had never worked on a Honda and needed a couple of days. He went way beyond the call the call of duty and in addition to fixing the clutch, affectionately cleaned the engine, and washed the car top to bottom. When I got it back, he thanked me profusely and said he couldn’t stop exploring the engine. I had a hunch and asked if he went to Cobre. “Yeah.” Did he ever have a teacher named Bob Cosgrove? “Yeah…He was different.”

Once we were clowning around, arguing about something, and I asked when I had ever lied to him. He said he didn’t think I ever had. Another time he told me he had been on a trip when his radiator broke down. It took him hours to fix it. “Oh that must have pissed you off.” “Why? Would that have fixed my radiator?” Two simple comments I’ve always held on to.

I don’t know that in my time in Bob’s orbit I ever said, “I want to be a teacher,” or “I want to be like Bob.” But on a different visit to Silver, I looked up some old friends. I thought they’d be surprised at my career choice, but one said, “That’s what you always wanted.”

I do know that I’m not a teacher like Bob, and I never ask myself what he would do. But at the end of every year, after handing in grades and packing up my lab, I look ahead and think.

Then I get out a blank sheet of paper, and sharpen my pencil.