It’s natural to think that the answers to today’s education questions lie somewhere on a continuum between two extremes: How much autonomy should students have – all or none? Hmmmm…. probably somewhere in the middle. Where should curriculum decisions be made – in my classroom or Washington, D.C.? Hmmmm… probably somewhere in the middle.

But finding the perfect compromise between two extremes can be fruitless and frustrating. Sometimes we need to stop and take a breath.

Let’s do it together.

Take a deep breath. Exhale. Again. Feels good, doesn’t it? Now take a deep breath and hold it. Don’t pass out! But hold it until it gets uncomfortable, then a little more, then exhale slowly. Feel the relief? Let it all out. All of it. Give it one last push. When your lungs are completely empty hold that state until it’s uncomfortable, then inhale and breathe normally.

Now, search for that perfect spot somewhere between breathing in and breathing out – The spot where you can just stop breathing forever.

Obviously, it doesn’t exist.

That’s because breathing isn’t a continuum, it’s a polarity. And readers of Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems, by Barry Johnson, will recognize the breathing illustration.

In a polarity, Johnson writes, there is no perfect midpoint. Both end members must be attended or the system collapses. If at any point in the process you stop breathing, you collapse!

Compare that to a continuum. I like blue but I’m not fond of yellow. Yet somewhere between blue and yellow, is green – my favorite color.

The breathing example demonstrates the salient features of a polarity: There is no sustainable mid-point, and you must spend time at each extreme. That’s not true of a continuum. Who really needs to spend time with yellow?

You solve a continuum issue but you manage a polarity, according to Johnson.

Here’s a classroom example of a continuum. An eighth grade team plans an incentive field trip. The team needs to decide how many unexcused tardies make a student ineligible. One teacher says a single unexcused tardy should disqualify a student. Another says they shouldn’t count tardies at all. Everyone else falls in between. The team agrees to vote on 0, 1, 2, 3… tardies and stand by the result. Issue resolved.

Now a polarity. How much should I review in Algebra? We need to move fast, and kids who need more time can go to tutoring, so maybe we shouldn’t review at all. Or, we could spend most of every class reviewing and add just a little new content at the end.

But locking into either is too rigid.

Here’s a better approach. In algebra new content builds on old and has review built in. So a class can go several days with little or no explicit review. But kids will eventually show signs of concept fatigue. When that happens it’s time for a couple of days of pure review.

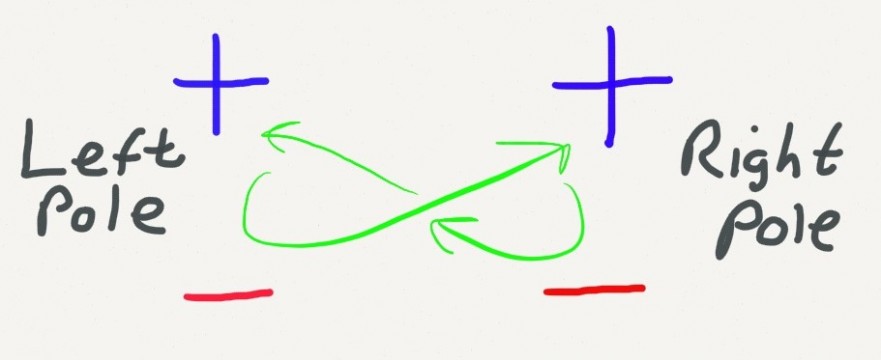

Good polarity managers, according to Johnson, can state the advantages and disadvantages of each end member. They also know what state the system is currently in, and what direction it’s moving. The aim is to keep the system in its current state as long as the advantages of that state outweigh its disadvantages. Then when the disadvantages begin to mount the task is to push the system to the other state. The drawing above, inspired by Johnson, illustrates this movement.

Pay attention to your breath for a few moments. Good polarity management is a marvel to behold.

We seem always to assume that hot button issues like teacher evaluation, Common Core, charter schools, vouchers, unions, and math instruction are continua. The result, therefore, is either winner take all or compromise. That’s fine if an issue is a continuum and the compromise is healthy or the winner correct. But if the issue is a polarity the system is doomed. (And if the system is a continuum but the compromise is unhealthy or the winner wrong, the system is also doomed.)

I’d ask advocates in any education issue to question whether the issue might be a polarity. If so, could they not indentify conditions when each end member is more suitable? Then could they not develop protocols for deciding which end member to move toward as conditions change?

On my Digressive Discourse Blog at The Center for Teaching Quality, please read in Common Core Math Instruction: Managing a Tri-polar System how I take a stab at how we might better manage teaching math facts, comprehension, and application – a hot button issue related to the Common Core.

Comments 2

Sandy — I read your CTQ article and it resonates with the ongoing discussion I participate in within middle school. Parents continually argue that their children do not need to understand concepts — just the algorithm. In some ways they argue this since many of them are engineers or other professionals and they understand the reality that in their job they simply apply algorithms and find answers. Many tell me that technology takes care of the conceptual problems. In many ways I have a hard time arguing with them. Your real world examples are ones similar to what I explain to students and parents. However, if students leave the K-12 environment and don’t see the usage of these concepts in their life have we wasted their time? I struggle with this question, but I appreciate you bringing this subject to the forefront of the CCSS debate.

Greg – How frustrating it is to hear about parents arguing that kids don’t need to know the concepts. Is that a consensus do you think? The loudest voices? Something else? I wonder if part of the aptitude of many engineers is that concepts come so easily to them, that they can’t accept the struggle some kids need to go through in order to understand. That sounds like I’m rationalizing, though.

It is a fair point they make that technology takes care of a lot of the calculations, but I’m not sure if I agree with that technology takes care of the concepts. Certainly not in any original work.