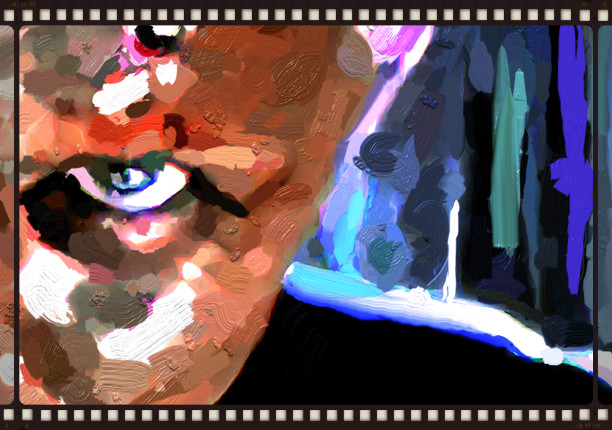

In Philip K. Dick’s iconic story, “Do Robots Dream of Electric Sheep?” and the subsequent film adaptation, “Blade Runner,” a theme that had appeared as far back as Genesis, and was later explored in the Jewish tales of the Golem, asked the question, “What happens when creations turn on their creators?” It is a timeless concern that is often explored in literature and film. However, is there a parallel narrative found in the interchange between education and society? I believe, that in a disturbing and twisted way, there is.

The replicants of Blade Runner rebelled because they began to think more deeply than their creators had intended. Through this realization, they turned on their programming and sought to destory their masters. In our case, our “creations,” are destroying us through the exact opposite theme: a lack of curiousity, apathy, and a failure to think deeply and critically.

Some argue that evidence of our biggest failures in education is found within the scores of standardized tests. Proponents of this case argue that our students can’t read, or that they can’t perform mathematical processes at an appropriate level. Although there are elements of truth in these claims, I would assert that such deficiencies pale in comparison to our students’ ultimate inability or unwillingness to think for themselves, to recognize learning and inquiry as enjoyable, identify their own biases and vulnerabilities, and to wake up everyday wondering, “What don’t I know?”

How has this happened? We have built an education system designed to cram as many “things” into the heads of our rapidly growing “creations” as possible. To program them. To pre-load their operating system software before adulthood, without an expectation that they learn how to perform the necessary upgrades to that system on their own, and without our guidance.

To learn on their own.

As a system, we don’t value or measure enthusiasm for learning. Contrarily, we often successfully “grade it out” of learners by creating a system of game playing, hoop jumping, and painful memorization of those “things” that students do not see as being personally relevant. As a ritualistic rite of passage, we think students should suffer as we have suffered.

How hard is it to learn content that you don’t see as important to your own purpose? You already know. Remember that workshop your district once sent you to, but that didn’t relate to your job? How engaged were you? What do those doodles on the conference center notepad say about the experience? Can you even find that notepad?

And, you’re an adult. Try being 12.

Some argue that suffering through tedium and arbitrary rules and expectations somehow prepares one for a life of tedium and arbitrary rules. How inspiring. I would counter that our charge is not to prepare children for the pain of the existing world, it’s to change and improve that world on a grand scale. After all, most of those society has identified as successful have done just that. They refuse to accept the status quo when the status quo can be improved. We are good at honoring these people, we’re just not very good at creating them.

How does this failure in institutional design come back to undermine us? Those who find inquiry as a chore want others to do their thinking, to tell them whether to be angry or happy, who to be afraid of, who to vote for, and what to buy. They take shortcuts. They respond with Pavlovian enthusiasm to “red meat” talking points and name-calling. They don’t look for information to form their own opinions based on evidence, especially if that evidence contradicts what they’ve already been told what to believe. They become the teacher who doesn’t see the need for conitnuous improvement, or to read a professional journal because they’ve reflected on their practice and found areas for growth. They become elected officials who lead with soundbites and idealogy. They become the obstructionist school board member that has no viable alternative plan rooted in the reality of the situation. They become voters, yet exercise this democratic right while remarkably misinformed, and then complain about the performance of the officials that they elected. In essence, they have become the antithesis of the Frankensteins of Blade Runner. Those Replicants attempted to dismantle modern society because of an increase in the depth of thought. Ours?

They are destroying us with their apathy.

Comments 3

I relate Clay Shirky’s story all the time, that he tells at the end of Cognitive Surplus. His young daughter went up to a TV and looked for the mouse. When she couldn’t find it she walked away. His point, quoting from memory, “Even a 3 year old knows that what’s targeted at me but doesn’t include me isn’t worth sitting still for.”

We don’t have to sit still for entertainment or education any more, nor do our students. If my presence doesn’t matter I can turn out and go away. I’m a huge believer that audiences – including our students – must contribute to our content as much as receive it.

WIll that fight apathy? I’m afraid not, but as Shirky also says, creating something bad is more cognitively satisfying than creating nothing, so who knows?

This was a super piece, Mike.

I have long held the belief that we don’t want our kids to learn to think. Even as adults we don’t necessarily do this well and often times let others do the thinking for us.

It is interesting to note this week while I was at the “Teaching and Learning Conference” and Bill Gates was asked the purpose of college. He quickly said “to get a job” but caught himself and engaged in a soliloquy about the college experience. I would say the purpose of school, whether you are in kindergarten or 7th grade or college, is to learn about the world and the role one plays in it. The purpose of school is to gain a deeper understanding of our history so that we can learn from it. The purpose of school is to be surrounded by diverse ideas and to engage with others who might think differently than you – and, from this experience begin to frame your own ideas.

We have one of the greatest democracies in the world and we squander it away in the guise of apathy.

Thanks for writing this and making me think a little harder tonight.

I agree with Kathy. People don’t necessarily want people to think. For all the talk of a critical thinking democracy, the reality is that an informed electorate can feel scary to some people.