This July marked the beginning of my 14th year teaching in Arizona. Born and raised in this state, it’s my 27th start of school in Arizona public schools. After a really hard 2021-2022 school year—staffing shortages, battles over curriculum, the continuing COVID pandemic, an overwhelming sense of burnout—I knew I needed to do something this past summer that I hadn’t done since I started teaching: I did nothing.

I’d always been the sort of teacher who signs up to fill their summer with additional work responsibilities, trainings, professional workshops, graduate school classes, and any number of teaching-adjacent activities, but last March I began a hard-fought campaign of saying “no, thank you” to all requests and forwarded emails, no matter how attractive the opportunity or how well-meaning the colleague. I needed a mini-sabbatical, a period of rest and time to unplug from being a teacher, and as summer inched closer and closer, I was increasingly excited about making it happen.

And then, just as our school year was wrapping up, the day before my high school students took their final exams and I could “clock out” for the year, an 18-year-old armed with two AR-15-style rifles jumped a fence at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas and killed 19 children and two adults. I remember listening to news accounts on my car radio, horrified and holding back tears while driving home.

That evening, our school district sent out an email assuring parents that exterior doors on all campuses would be locked for the last two days of classes. As teachers, we silently pondered the likelihood of copycat events while worrying about whether our students would feel safe enough to come to school to take their final exams. (They did, for better or worse.)

Although the media coverage could feel near inescapable, I managed to live in a bit of a bubble over the next few weeks—avoiding the news, binging on streaming television, and indulging in long, alarmless midday naps. I took an extended vacation out of town and let myself stop thinking about school for a few short weeks, luxuriating in the feeling of being responsible for and to only myself.

But even while my “teacher brain” hibernated, things were changing. Over the summer, new door alarms were installed on the exterior doors of my school building that faced a busy major street.

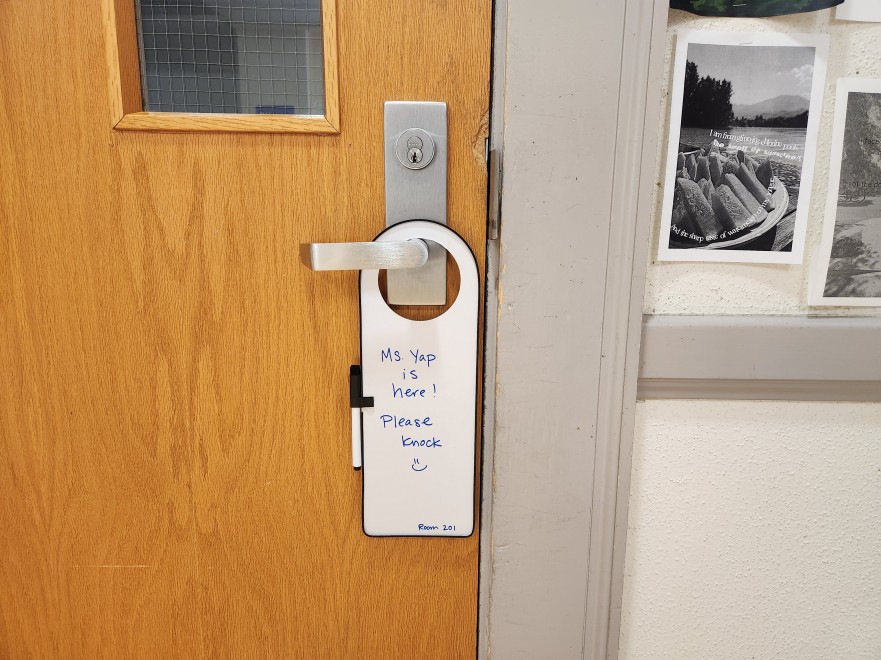

Two days before we opened our doors before the first day of school, we received an email from our principal: in accordance with a new district mandate, all classroom doors must be locked and shut at all times during school hours. All staff were instructed to wear their ID badges visibly on their person at all times.

A new campus-wide security plan was distributed with annotated maps showing which exterior gates and doors would be locked at particular times of the day, reducing the points of entry to buildings. Our school resource officer encouraged interested staff members to join the school safety committee on Thursdays after school. Another email went out with details of the new centralized “dispatch” phone number for security issues. A new color-coded hall pass system was rolled out across campus to replace our previous admittedly haphazard approach, a patchwork of paper passes, plastic clipboards, wooden plaques, and, notably, one small carved weiner dog.

Anyone who has ever worked at a large, busy high school can imagine how well the new locked door policy went over. Teachers who were accustomed to propping their doors open all day grumbled about airflow and having to let students in and out for tardies and bathroom breaks. Students who had the misfortune of being seated closest to their classroom doors became de facto door attendants, interrupting their notetaking or essay-writing every few minutes to heed the tap of a sheepish classmate returning from the drinking fountain. Even after the final bell, the flow of students stopping by after school for tutoring or to ask questions dwindled, then stopped almost completely when we were told that all doors needed to be locked after school hours as well.

I remember there was much discussion in the days immediately after the tragedy in Uvalde about locked doors. Law enforcement in Uvalde initially claimed a teacher at Robb Elementary left a door propped open with a rock, then said it was closed but unlocked, then admitted it was closed but the lock failed, allowing the gunman to enter the school building. A few months later in an interview with NPR, the city manager of Uvalde referred to increasing the presence of law enforcement on campus and “harden[ing] targets” as measures to help students and families feel safe in coming back to school again.

I don’t like being a target. I don’t want to be hardened.

As an English teacher, I’ve been trained to understand the power of a symbol. That sometimes even the most well-meaning or practical of gestures can take on a meaning beyond the literal. Sometimes a door is a door is a door. But these days, I wonder what my locked door says to my students about the classroom they are entering. I wonder how it feels to be asked to read and write and think and talk in conspicuously closed spaces. I wonder what we gain, and what we lose, when we tell our students the best we can do is lock the door behind them when they leave.

Comments 1

I am going to have to sit with this blog for a bit. Just thinking about all of the locked doors on a campus breaks my heart. Students should feel safe and secure at schools; not locked down.